How I became a ‘D-Day Dodger’ by Edward Carr 13th Foot – Somerset Light Infantry

Edward Carr (aged late-80s)

13th Foot – Somerset Light Infantry

I call this narrative, “How I became a “D-Day Dodger”, and it is also my tribute to all the many thousands who gave their lives in this extremely bloody war and who got very little recognition for it.

After four weeks of training with the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, I was transferred to the Somerset Light Infantry and undertook battalion training, which was learning to move and fight as a group of about 1000 men. We learned street fighting amongst ruined streets in Great Yarmouth; learned to live off the land and to live in the open air in all kinds of weather. We also learned unarmed combat and how to move silently and not be seen in open country. As an exercise we had to make our own way to a new camp in Sussex – the home guard and army would try to “capture” us.

I was put through training in landing craft on the beach at Clacton-on-Sea. The landing craft were flat-bottomed boats with sides which pulled up and were held in place by hinged pieces of wood, wedged under the rim of the boat to hold the sides in place. This type of craft was more suited to rivers than sea – we paddled them out and, as we turned round to paddle back in the sea, would collapse the sides and men would be thrown into the sea! It was impossible to keep the sides up!

On another course in Ballymena, County Antrim, we were taught how to use the weapons which were being used by the enemy. If enemy weapons were at our disposal we would need to be able to use them. I must comment that, personally, I found the German Spandau machine gun to be the most accurate and fastest.

After returning to my unit in Clacton, orders came through to say we were going overseas. The second front had not yet started.

We arrived at Southampton and boarded The Dunotter Castle, being issued a life jacket and hammock each. It took 24 hours to fill the boat with troops and nurses; they included French Moroccan, Canadians, New Zealanders, Indians and Gurkhas.

At dusk about 48 hours later we arrived in Taranto harbour (right in the “instep” of Italy), disembarking around midnight. We were now part of the 4th British division. The 4th Indian Division would be with us for our time in Italy and later on in Greece.

We began to move up the east coast through Bari and Capua, a small town south of Cassino. This was our destination and the rest of our forces would arrive later on.

Sgt Carr 1st Somerset Light Infantry using Bren gun in the ruins of Cassino town. (Note the hole in right boot!)

The first battle involved allied armies who had advanced more or less unopposed, then come across prepared defences of the Gustav Line. The Americans had planned to cross the River Rapido (which was 60 feet wide, 9 feet deep and had a current of around 8 mph, with vertical banks of about 2 or 3 feet above water level). Continuous rain and flooding by the Germans, as part of their defences, had made meadow land into marshland and mud. The Yanks had bombarded the German positions as they advanced, but as they neared the river, they could not depress their guns enough to engage the enemy.

They suffered casualties from minefields which should have been cleared as they advanced. Mortars and gunners had open day; shrapnel and bullet holes made a lot of the boats useless. In the pouring rain and pitch black of night, a lot of the guides lost their way, some got separated from their units and got lost. Their commanding officer and second in command were among the first casualties. The rest of the force attempted to cross the river without artillery support in the face of murderous enemy fire. Alerted by the noise of the confused approach, the enemy (despite the dark and rain) poured fire into the crossing places. Many boats were sunk, others capsized as men climbed into them under heavy fire. Two companies managed to get across and attack enemy positions, while the engineers attempted to put footbridges across for troops that were to follow. Enemy fire knocked out two of the bridges and one was destroyed by mines. Two companies got across before the only remaining bridge was destroyed by enemy fire. By dawn, with no communications of any kind with the troops who had crossed, the Yanks found themselves with their backs to the river, surrounded by self-propelled guns and German tanks, who systematically began to wipe out the American force.

The American officer in command asked permission to withdraw but was refused. Before he had that reply he had already ordered a withdrawal on his own responsibility. In the morning, the commanding officer ordered the rest of the Americans to make a crossing of the river under cover of a smoke screen. A footbridge had been erected and a third battalion was across before midnight, and by dawn the following day another three battalions had crossed, including the one that had withdrawn the night before. During the morning, when the mist lifted, the Germans destroyed the footbridge, remaining boats and the telephone lines. Pockets of men held on for a while, but then the volume of fire died down and by 4pm it was all over.

In 48 hours, the Americans had lost 1681 men dead and 875 missing. It was the worst single loss in battle since Pearl Harbour.

While this had been going on, our battalion was involved in patrols, testing out enemy strong points to keep the top brass happy. A New Zealand division, American 1st Armoured Division and the 4th Indian Division had joined us, so we knew something was in the wind.

Having been ordered to approach the railway station via a shallow causeway close to Monte Trocchio, we came across a storm drain running under the road in which Italian women and children were crammed. We tried to get them to go down to the sea to escape because shells and mortars were falling along the road – one hit on the drain and they would all have been killed. They seemed to prefer to stay, but on passing the spot several weeks later, there was only part of the road left so we never knew if they managed to escape.

Next day we got word the abbey was to be bombed. German positions were all around the abbey on the hillsides. The advance to the railway station was stopped and positions consolidated. We had to move with great caution – German snipers were very good. I once had a go with one of their rifles – at 300 yards using the special sight you could pick out facial details – it was very accurate but had a kick like a mule!

We entered a small farmhouse whose occupants had left in a hurry – a pan of spaghetti was still cooking on the stove. Two of our lads tried it – after waiting an hour to see if the lads hadn’t been poisoned, we all tucked in! We took up positions, lookout and sentry. Suddenly the cellar door burst open and German soldiers came out with their hands in the air! They must have thought our whole battalion was there to give themselves up and looked surprised when they saw we were just a small platoon. Checked for weapons, they were locked in a room with a guard. HQ was pleased to hear of our 27 prisoners. It was a lesson we didn’t forget; don’t make yourself at home in a house until you have checked the cellar!

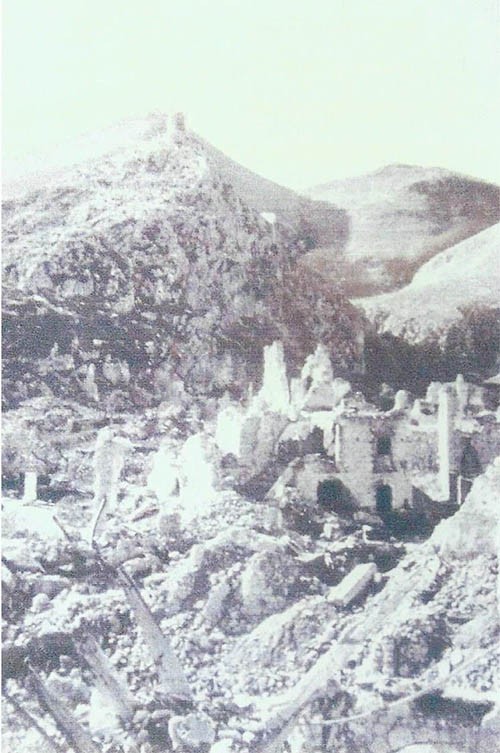

The morning of the bombing was sunny. We could hear aircraft very high up and see vapour trails of a lot of aircraft. We saw the bombs falling and as they exploded, huge clouds of dust rose up from the abbey. A few missed the target and fell on Snakes Head, a hill near the abbey, occupied by Americans. Three waves of bombs fell, some hitting the town of Cassino, parts of which were occupied by our mob and the Shropshires. The next wave included Mitchells (medium bombers). The bombing continued for most of the day and by dusk the abbey had been reduced, along with the town itself, to great piles of rubble. The abbey was almost unrecognisable. The shape had changed; the square cut walls had gone, with a huge pile of rubble in the centre.

The next day some fighter bombers flew over, which I assumed were taking photos; apart from that there was no air activity at all. No event of the war caused more heated controversy than the bombing of the abbey. General Mark Clark, wrote after the war in his memoirs: “I say the bombing of the abbey was a mistake”. My personal view is that it made the job more difficult and costly in terms of men, machines and time. Afterwards, it was reasonably well established that the abbey had not been occupied by German troops at the time of the bombing. However, this could not have been known at the time. The piece of ground called Monte Cassino, a 1,700 foot mountain with rocky sides, a zig-zag roadway, providing shelter for tanks and guns, was a powerful fortress. In military terms this was called, ‘a single piece of ground’.

THE SECOND BATTLE

The morning of the attack found the troops of the 4th Indian and 4th British divisions facing another day that was unlike any we had experienced before. Only a jagged lump, which was formerly known as the town of Cassino, separated the forward positions from the Germans. The New Zealanders were on our left this time. They were, in my opinion, some of the best soldiers you could wish to fight with. Our Colonel Hunt said to the officer commanding the Kiwis (New Zealanders): “Your men don’t salute much do they?”. The officer replied, “Try waving, they always wave back!”. By the time we left our rest area, the winter weather was worsening; rain, sleet and snow with a bit of hail was making the ground in the flatter areas, a wasteland of mud, marsh and flood.

The attack had been ordered to start at 23.00 hours, but the mules bringing the ammunition had not arrived. In the mountainous country you could not use trucks because they would be spotted and blown off the road. All our supplies, from ammunition to water to petrol, had to be brought seven miles across the valley on mules, then man-handled the last few yards to the forward positions. The supply route took five hours to cover and was shelled most of the way, so only a small percentage of the mules ever got through. On many nights the wounded had to endure the same long journey in the opposite direction.

It was well after midnight when the attack eventually started. I remember the RSM saying, “Try and wait until the enemy is standing one in front of another, that way you will get two with one bullet!”. He had said this because most of our ammunition was at the bottom of Bari Harbour. He could always be relied upon to bring a smile to the lads’ faces. Our objective was to cross the river on the east side of Cassino where, since the bombing, the water level had dropped 2 – 3 feet, so it was possible to wade across.

The 4th Indian Division and the Polish were putting in an attack on higher ground to our right. As we approached the river, it looked different to when I had passed that way on a patrol a few days earlier. There was a patch of scrub about 50 yards back from the far bank which I could not remember. I mentioned this to platoon commander Lieutenant Bashley. He said, “You must be mistaken, probably it was another place you remember”. We got across the river without opposition which was odd, but as the leading section approached the scrub there were explosions. It was not scrub at all, but a strong thicket of thorns that Gerry (the Germans) had dragged there. It was reinforced barbed wire and anti-personnel mines. As those that had not been hit ran for cover, there was a shower of grenades from the other side of the ‘thicket’ followed by fire from Spandaus, which were Gerry machine guns. Someone had ordered smoke, and as the smoke bombs came down, we withdrew back across the river. We carried the wounded back with us, one of them being Lt. Bashley. Most of his left leg had been blown off, his face was badly disfigured and some of his innards were hanging out. Somehow, he was still alive. I never knew if he survived or not. Sometime later, our artillery pounded the spot until it was just a heap of mud. A and D companies went through and consolidated the position. The action that went down was a skirmish.

I had to go to HQ to report as the most senior NCO surviving. We lost 8 dead and had 7 wounded as well as 3 walking wounded. I was made up to ‘WS/Sgt’ which means, ‘War Substantiated Platoon Sergeant promoted in the field’; a good rank to have.

It had been a bad night all round; the Gurkhas had lost 11 officers and 135 men. The Indian Rifles had lost 196 men and officers. The RSM said, “Your platoon is 19 men short, so with two other platoons in the same boat, we are making them into one platoon until we get reinforcement. You are being seconded to 1st/2nd Gurkhas, it will be a good experience for you”. At the time I didn’t think so, but later on I had to agree with him.

I located the quartermaster’s store – it was like Aladin’s cave! I had my 3 stripes issued and new battle dress top. The quartermaster said, “One of my lads will sew them on for you”. This was quite a surprise being used to doing my own sewing. That extra stripe made all the difference!

I met my new platoon, introducing myself to everyone, shaking hands – even though I knew I would never remember all their names. I was told their nick-name for me was, “Cpl Gun”, because I always carried a Bren gun! I soon settled in with them – they were real soldiers in every sense of the word.

My next job was to go with a priest and several of my men from my new platoon, to move six nuns from a convent close to Cassino on Route 6. The convent was needed as a casualty clearing station, so the nuns were to be moved to a safer place, another convent at Pletoni, about an hour’s drive away. The roads were not good; we got stuck twice and the second time everyone had to get out and push. The weather was really cold and one of the nuns had bare feet. As we got back into the truck, one of the Gurkhas gave the nun a pair of his socks from his backpack. They were bright red (his good luck colour). The priest said, “I bet she is the only nun in Italy with red socks!”.

We delivered the nuns safely and headed back before it got light. On the way, one of the Gurkhas said, “Pull under that tree and wait for us for 20 minutes” – they returned about 10 minutes later with a tin hat full of eggs and two chickens that had not been dead long, and presented them to the priest. As we dropped the priest off he said, “I’m glad you were with me, I was a bit frightened of those men!”. Later, as we ate the eggs, I told the men what the priest had said – they roared with laughter and said, “We were nervous of him, that’s why we got him the chickens!”.

In the next two weeks I went on many patrols with my Gurkha platoon and the more I got to know them, the more I admired them as soldiers. We were in a part of Cassino that had been full of houses. There were no large buildings and sometimes at night, you could hear the enemy talking on the other side of the wall. When the Gurkhas heard this, they would slide away into the darkness. The talking would stop; the men would return giving the thumbs-up sign – another job done!

German ground forces were making it impossible to move round. The top brass had decided to let the F.A.F. boys help out. We pulled back to pre-arranged positions and hoped the bombers got the markers right. We heard them coming in a long time before we saw them. There seemed to be dozens of them; there was no anti-aircraft fire and no enemy fighters. We could see bombs falling – then the noise started. Continuous roar and crump – the funny sound a bomb makes when it explodes in a building. It was murderous bombing, scientific; the sound waves moved away and all that was left were great clouds of dust and flames. Word came through we were going in to mop up any remains. As we advanced, Gerries popped up from every rock and brick, some crawling out of holes in the rubble, still firing their guns. They were trying to counter-attack, but the bombing had shaken them and they were not organised. One by one, the pockets of enemy were cleared out. There were no prisoners – they fought to the last man. One Gerry, with no weapons left, stood there waiting to die. One of the Gurkhas said to him, “Get the hell out of here fast”. The Gerry faced us and shouted, “Sieg Heil, Sieg Heil”. Not another word did he say – from behind came the rattle of machine gun and the German soldier collapsed among his comrades.

Between patrols, feeding and trying to keep dry and warm was just about impossible. The rain never seemed to stop and our living conditions had got worse. The whole of our front line was overlooked and the enemy held heights on three sides. There were unburied and unreachable corpses – it was one place we wanted to get away from. We all feared the smaller mines (the “S” mine sat in the ground with three bits of steel wire sticking up – if you stood on one of the bits of wire it would set off the detonator). The one-second fuse would pop then explode, and the mine would jump 3 – 5 feet in the air and then explode again. These mines were filled with ball bearings, which could strip flesh from bones. If you were lucky and heard it pop as you stood on it, you could drop flat, face down, and the thing would explode above your back – (all being well).

I was hospitalized with a bout of pneumonia and fortunately with medication, bed rest, food and clean dry clothes, was able to return to my unit just as reinforcements from Oxs and Bucks and also Cornwall Light Infantry came to join my regiment, making us a full platoon. We also had a new platoon commander (Lieutenant Young). I was tasked with taking him to show him the part of Cassino we controlled. I pointed out the abbey, Hangman’s Hill, Castle Hill and one or two reference points we used just to give him a general picture of what was happening. I advised him not to wear a tie, leave his map case in his gear and to put his binoculars in with the radio his “batman” carried. (The reason for this was the Gerry snipers were very good and those were the things they looked for).

I went with the three new corporals to do a patrol of Castle Hill. On the outskirts of Cassino a barrage started. It seemed every gun was pointed at us; mortars and 88s exploding coming towards us. I was blown backwards from a blast into a shell hole. There was water to knee height and a rat ran in front making me jump. As I crawled out of the hole I came face to face with a Gerry. Fortunately for me one of my men had seen what was happening and shot the Gerry, killing him and saved my life. Of the ten who set out on patrol only five came back.

The next day we were to have a spell at the station – taking over from the Hampshires. It gave a funny feeling at the bottom of your stomach to hear tanks going by on the other side of the hill, not knowing if they would suddenly appear. Worst of all though were the flame throwers. They could spit flames for 200 yards. The liquid (like thick jelly) burned if you were hit with a small amount. We were given the task of retrieving the wounded off the battlefield and one of the wounded brought in was ‘Dapper’ (so named because he dressed well) – a man I had served with from my early days and the soldier who had saved my life only two days ago. I tried to comfort him, but he slipped away from us. Many years later when I returned to Cassino on a pilgrimage I saw his grave.

THE THIRD BATTLE

Once it had been realised that the last attack on Cassino had failed, the next battle was planned. It was about the same time as the German onslaught against the bridgehead at Anzio had reached its climax and the attack had been halted. This time the New Zealanders would be attacking the bottle-neck of the town and Monastery Hill, the 4th British and 4th Indian Divisions would storm the steep mountainside of Monastery Hill.

The attack was to be preceded by such a bombing as had never been attempted in front-line history. An obliteration of a small infantry objective was to be carried out by heavy bombers. Cassino was officially cleared of civilians (which it was not) and was now classified as a fortified town stretching half a mile square. General Alexander said this operation (Operation Dickens, with code name Bradman, after the cricketer) would be studied with an eye to future operations in Europe.

While we all waited in the exposed valley, wet, frozen and on edge, the heavens opened again. It poured with rain every day for three weeks. Operation Dickens kept being postponed. Every morning the password would go out: ‘Bradman was not batting today’. During the three weeks of waiting, the enemy continued shelling, which took its daily toll. In those three weeks the New Zealanders lost 363 men, the Indians and the British the same. It was now March and some dry weather was forecast. During the night the foremost infantry units slowly filtered back to what was supposed to be the safety line. A few suicide squads were left to keep firing the odd round to give the impression of business as usual in the temporarily empty posts.

On the stroke of 08.30 hours the first flying fortress appeared over the town, spout after spout of black smoke leapt into the air from the town itself. Time and again we watched the bombs explode. There was a little half-hearted ‘ack-ack’ at first, then it went quiet. One flight dropped its bombs on a village called Venafru 15 miles away. We learned later it killed 140 civilians. One bomb hit the Moroccan hospital, killing another 40. There were another 40 casualties in the allied artillery lines and a string of bombs straddled the 8th army HQ. As luck would have it, no senior brass were there. The CSM gave a quote from the Duke of Wellington’s speech after reviewing his troops saying, “I don’t know how they will impress the enemy, but they frighten me to death”; this summed up the raid OK.

While the bombing was going on, 7th Brigade of the Indian Division were stuck on Snake’s Head Ridge. They hadn’t had supplies of food or ammunition and had been sniped at all the time, which meant they could not get out to remove their dead from the previous battle, making the air around their positions almost unbearable. We envied the British bombers that had flown out from England – dropped their bombs, then headed out over the Mediterranean to North Africa, refuelled there, then back to their bases in England. If they didn’t get shot down on the way they’d be home for a late tea and then a nice dry bed!

At noon, bombing stopped and the Kiwis led the way back into Cassino town following a creeping barrage. The only way forward was to hold the bayonet scabbard of the man in front. The rain by now was a torrential downpour, filling in the craters, creating small lakes and, in between the rubble, a muddy, stinky mess. Our boots, socks and battledress were soaked. For many of the men it was their first bit of action and being soaked to the skin they weren’t very happy. The town, as we moved back, was an unbelievable mess. There were no roads or tracks left that you could pick out; just heaps of rubble with the odd wall sticking up and craters everywhere that needed use of hands and feet to get in or out. If you slipped into one with all your equipment on, you even stood a chance of drowning! All the sketches we had made before the bombing were now useless.

The enemy was in the remains of the Continental Plaza Hotel, a Plaza called: “the Baron’s Place”, and they were also in the ruins of a hotel called: “Des Roses”. Our radios weren’t working very well having been dipped in and out of water. There was one bit of good news though; earlier on, we could see figures moving and found it was the Gurkha regiment which had kept going during the bombing, and had walked through the German positions and reached the Indians who were isolated, replenishing them with supplies. Our objective again, was the railway station. I had been in and out of there so often it was like an old friend. It was now Friday; the battle had started on Wednesday and today we were with the Essex regiment on our right and the Kiwis on our left. As we picked our way across the rubble, a Gerry patrol appeared. Corporal Wright let fly at the same time as I did. Three dropped and the others took cover. Lieutenant Young shouted, “Grenades! Over there!”, and one or two lads lobbed some in the Gerries’ direction. We were lucky, that put paid to what was left. We went over to look at them, it was the first time some of the lads had seen a Gerry close up; usually it was 50 – 100 yards down the barrel of their rifles. Their insignia told us they were of the 1st Parachute Regiment (some of Hitler’s crack troops). This cheered the lads up to think they had come off best against some crack troops!

The Germans made an attack next, breaking cover from Monastery Hill. From the first hairpin bend where there was plenty of cover, they came running down, with tanks on the road above them giving covering fire. Before they reached the station the attack petered out because of tremendous fire from all three units on our side, which had the support of the Kiwi tanks. The remainder fell back to the hairpin bend, leaving a lot of dead. They tried again later, but were driven back again. A wounded Gerry said they had lost about 200 men in the first attack – they did not know we were so strong on the ground. The Kiwis took over the station and we worked our way back to the area of the Continental hotel (I don’t know why we called it the Continental – its real name was Excelsior!). We now held a large part of the town, Castle Hill and, at the moment, the railway station.

After an attack next morning which we rebuffed, we had several pockets of Germans who surrendered, as well as some Italians who, even though they surrendered to the allies, were still fighting with the Germans.

Eventually the Gurkhas and Indians had to be withdrawn from Hangman’s Hill because they couldn’t be supplied. Out of 400 that went up 7 days before, 8 officers and 177 other ranks came down the mountain between two walls of artillery fire. Sunday afternoon saw the end of the third phase of the battle; the turning point. The German 1st Parachute Division and the Monastery had won again.

Handling of casualties at Cassino was a huge problem. Men wounded in the mountains had to be carried down terrible paths for two miles. The only way it could be done was to establish a chain of stretcher-bearer posts every 200 yards down to the valley. That took several hours because of the difficulty of descent and delays caused by constant harassing by German artillery and mortars. This stage was followed by mule transportation for another five hours to a field dressing station. Stretchers were constantly put down or tilted as either the bearers or mules stumbled or slipped on the terrain. Night temperatures were generally well below zero and the task frequently took place in rain, sleet or snow. Sometimes stretcher bearers and mules were hit by enemy fire.

A lot of wounded did not survive these trips, so surgical units were set up very close to the front under canvas or equipped trucks with full surgical facilities, including blood transfusion services. This saved a lot of lives. Because of the high number of head and eye injuries, a forward head and eye injury unit, with a higher than usual number of specialists, was also established.

Restriction on daylight movement led gradually to a practice of openly evacuating men in daylight under the Red Cross flag. Nothing was officially arranged, but it was done. Both sides respected the Red Cross. At times, we were only 100 yards from the enemy. Stretcher-bearers of both sides made daylight trips into ‘no man’s land’ to collect the wounded and sometimes they exchanged words! This was Cassino; a battlefield on which, for weeks, the dead could not be moved or buried. On Snake’s Head Ridge, the Royal Sussex rescued many of their wounded under the Red Cross flag. The dead were sent down every night on the back of mules which had taken up their food, water and ammunition.

THE FOURTH BATTLE

Another attack was on the way. We didn’t know at the time that this was the fourth and last battle for Monte Cassino. A lot of planning had gone into this attack, more than for previous ones. A lot of movement had gone on but it had only been done at night. If an armoured unit moved, it left behind dummy tanks and vehicles. Artillery was moved up, hidden and not brought into use. To assist with the projected crossing of the Rapido river, many tracks had been repaired or improved and many new ones laid. All this work was done at night and, before the area was vacated at first light, new tracks would be carefully hidden with brushwood or some other camouflage materials.

An extra four divisions of the French Expeditionary Force had been packed into a small bridgehead at Garigliano, and two Canadian divisions hidden in the Liri valley. Word came up that General Alexander was going to, “give it all he had”; he was going to give the Germans a taste of Blitzkrieg, that they had so often handed out.

It had been sunny for many days and the valleys were turning green, but all around Cassino and the monastery there were no trees, just hundreds of stumps. Up and down the line, tension was building up. While you lay there (we worked all night) you got some rest, but a lot of the time you wondered how you would do in the coming battle. Would your luck hold out? I had been lucky up to now. Apart from Bill Wrightson in my platoon, there was only Harry Abba (who was now a sergeant in ‘A’ Company) that had set off with me from Tarranto. The rest had either been wounded and finished up somewhere else, or had been killed and would be buried in a cemetery out here.

At 23.00 hours the artillery tore the quiet of the night to bits. I learned afterwards that there were 1600 guns. As you looked back, there was a flickering line of hills; ahead the valleys and ravines echoed and re-echoed to the crash of shells with the continuous sound of thunder and the scream of the shells as they passed overhead. We were glad we were not at the receiving end of that lot! Smoke was everywhere. Different commanders had ordered smoke-screens to be laid without consulting each other. This ended up with so much smoke that no one could see anything! We crossed the river with the Indians and established a bridgehead of sorts. We were pinned down, hanging on by the skin of our teeth. The enemy was constantly attacking. We needed some support. To the astonishment of the troops on the ground, a tank moved up slowly to the river bank behind us, carrying a bailey bridge on its hull. This was followed by a second tank with its front coupled to the end of the bridge. The first tank dipped into the river and slowly drove to the middle and sank whilst the crew “abandoned ship”. The second tank then slowly pushed the bridge across to our bank where it was quickly secured. The Canadian tank men and engineers had done a tremendous job; within minutes tanks were coming across and were blasting enemy positions. The bridgehead was now secure.

Whilst this was going on, the Polish had begun to pick their way through the boulders and thickets and the gruesome debris of the previous battles. Through the corpses that still littered the ground and the machine guns that seemed to have grown out of the rocks; they were being mown down like nine pins. Just as the Yanks, Brits and Indians did, they just kept going; fighting hand-to-hand and finally reaching their objective. When daybreak came, only a handful of men was left and as the sun came up, the enemy picked them off one by one as there was little cover. They could not be reinforced or supplied. They were on their own and didn’t get the order to withdraw until late in the afternoon. They had done an outstanding job at a huge loss, but they had given the British, Indians and French that bit of extra time to do their job. The bridgehead across the Rapido was slowly increasing. The idea was to keep going and encircle Cassino, to keep attacking day and night, accepting heavier casualties than the enemy, until there wasn’t enough enemy to hold on any longer.

At 10.30 hours on 18th May, a Polish detachment marched across the slope from Point 593 and occupied what was left of the abbey of Monte Cassino. The Germans had pulled out during the night before and escaped in the darkness leaving behind a few badly wounded men and two Hitler youths, whom the SS had nailed to the great doors which still stood. This was a lesson from the SS for not fighting hard enough! They were only 14 or 15 years of age and both very dead!

All of a sudden, it didn’t matter anymore. Cassino was just a name on a map. Down in the valley the entire might of the 5th and 8th Armies were streaming across the bridge over the Rapido River in a constant stream of traffic which lasted for days. The leaders had, by now, reached the next line of defence called the “Adolf Hitler Line”, but were being held up by extensive minefields and chains of pill boxes in areas fortified up to a depth of 1000 yards. In the meantime, the main body of the army was held up getting through Cassino and over bridges; 2,000 tanks and 20,000 vehicles and a lot of men. Let someone else sort it out!

The Polish army had put up a memorial on the hill point called 593. This has now become the Polish cemetery and when I visited in 2007 the memorial reads: “We, the Polish soldiers, for our freedom and yours, have given our souls to God, our bodies to the soil of Italy and our hearts to Poland“. These words describe the gallantry of the Polish armies in Italy.

On 6th June 1944 the Allies landed in Normandy and so Italy was no longer front page news. While we were collecting our dead comrades and generally taking stock of ourselves, I had a trip down to battalion Headquarters. Colonel Hunt, our commanding officer, had requested my presence. In due course I was ushered into his presence by the RSM. The commanding officer asked me if I would be interested in attending Officer Command Training Unit as he thought I had officer qualifications. I politely refused saying that I would rather stay in the ranks and remain with my platoon.

That night I attended the first and only show I saw in Italy; the acts were The Andrews Sisters, followed by a comedian, but the star of the show was Al Jolson. I had heard my dad talk about him because he made the first talking picture. After he had sung two songs, he said, “You are sitting in the rain to hear me sing, so I’ll join you in the rain!”. He came out from the cover and stood with the rain falling on him and asked us what we wanted him to sing. He sang for about an hour and everyone stood up and cheered him.

During the next week or so, we were given a new job. The area around Cassino and the Liri Valley was a strong fascist part of Italy. Our job was to get rid of fascist books from the public libraries. We had to pile them in the town square or similar place. Someone speaking Italian would tell the locals gathered there that the rule of Mussolini would never come back again. When the speech was over one of the lads would step forward with a flamethrower and set fire to the lot. The local mayor would thank us, and that was that! It went down very well and we had done more than 25 different places when we came to Caserta. It had been Allied Headquarters, but just south of the town there had been a prisoner of war camp, holding British and Polish soldiers, taken prisoner in North Africa and transported to Italy. The Italians had badly treated the prisoners, making them work long hours and feeding them on potato peelings and scraps of food, only fit to be thrown away. This treatment had altered as the Italians changed sides, but it hadn’t been forgotten. One or two people in charge there were eventually sent away for war crimes.

We did the usual routine of piling up the books, the speeches were made and the flamethrower made his shot. However, this time it didn’t ignite, so he gave it another burst. This one ignited but bounced off the top of the pile and landed among the Italian dignitaries. We were accused by the locals of doing this on purpose, but it was truly an accident. When I revisited the town in 2007 it was the only war grave cemetery that had its gates locked due to the damage being done to the graves.

As the second front was established in Europe, the top brass decided to withdraw most of the ground forces from Italy. The 5th army had to withdraw seven of its best divisions; three American and four French divisions. Once again the troops in Italy were being robbed of total victory. It was a poor reward for the troops in Italy. Cassino, so costly in human life and suffering, was to be deprived of the full victory that would have made it worthwhile in the end. Now it was little more than a victory of human spirit for the common soldier, and a memorial to the horrors of war. As for our battalion, we were moved across to the west of Route 6 and proceeded northwards in a general mopping-up operation. Most of the hard fighting was continuing to the east of the country. Impregnable Cassino had fallen, two German armies had been thoroughly defeated, 20,000 prisoners were taken, three defence lines were smashed, vast quantities of tanks and guns had been destroyed and two Allied armies had advanced eighty miles! We continued on our way and ended up in Milan, where we got new orders to leave Italy.

This narrative is taken from an account of my time spent during the 1939-1945 Second World War and is printed here with my express permission to the Italy Star Association 1943-1945.

It was written on the advice of the Royal British Legion, to enable future generations to understand how we of that time lived, and sometimes died, during that proud period of our history.

A full copy of this narrative now lies in Hull City Museum archives.

I have given my permission for the Italy Star Association 1943-1945 to use part of my account and put it on to its web site – Signed: Edward Carr.

What a fine report. My late Father flew “the boys back from Bari” some of them, at least!

My late father, Ernie Miller, wrote a book called “Diary of a D-day Dodger” which follows his war time in the Army with the REME going up through Italy.